Children are the most affected group — they’ve not only left their homes but lost years of education, access to health and proper nutrition. Though many humanitarian assessments were conducted in previous years to understand the extent of the impact of conflict on displaced and affected populations — no nationally representative survey of Iraq was conducted in the last 6 years to measure poverty.

Why? One of the challenges that development practitioners face in Iraq is how to regularly monitor child poverty when surveys to estimate child poverty are expensive and often infeasible. And even when regular surveys are feasible, it is extremely challenging to ensure that they’re representative at the district or sub-district level with right sample size. In addition, no regular poverty monitoring mechanisms are in place this means that poverty rates in country have not been updated (even though efforts are being made by the Government of Iraq to update the poverty estimate through SWIFT survey in 2018).

To help us realize children’s rights and address the rapidly growing challenges facing children (especially around poverty, education, nutrition and health) — we need accurate and timely estimates of poverty, and to understand how these figures have changed during the recent periods of conflict and economic slowdown.

UNICEF Iraq in collaboration with the Government of Iraq (GoI), Zain, and UNICEF’s Office of Innovation are working together to look beyond traditional methods of measuring poverty — starting with collecting and analyzing available data sources such as mobile data, satellite imagery, and exploring how to integrate high frequency surveys. The aim of this collaboration is to test whether cell phone data (CDR) and satellite imagery are sufficiently good predictors of poverty. Once the relationship is established and a model is developed, this can then be used to monitor and update child poverty estimates for Iraq on a regular basis.

To shed more light, UNICEF Iraq’s social policy team, Atif Khurshid (AK) and Khulood Malik (KM) and UNICEF Innovation’s Research Scientist Vedran Sekara (VS) share more information about the project and identify the opportunities that frontier technology & data science can bring to monitoring child poverty in Iraq.

Can you share a bit more about this project? What makes this different from traditional data collection?

VS: Traditionally, poverty data is collected using surveys, meaning the government, UNICEF, the World Bank, or some other entity go from household to household and ask the residents questions in order to collect data. And this has to be done in a way that is representative of the population. This is a very laborious, slow, and expensive process, as such surveys are only done once every 5-10 years and sometimes every 20 years! Of course, population changes more rapidly, and it’s accelerated due to different events, such as natural or human made disasters, that can affect large scale populations on much faster temporal scales. Nowadays around 66% (and counting) of people on earth own and use mobile phones. Our interactions with mobile service providers leave a lot of digital breadcrumbs which can be used to estimate socio-economic indicators. Aggregated calling behaviors of regions — such as when people on average wake up (and start calling) and the percentage of international calls — are variables which, when combined with others, can be indicators of child poverty in a scalable and real-time manner.

KM: Take for example in Iraq: the government can only conduct surveys in 4-5 year intervals. This is a big issue — where we need to be informed about poverty rates in different regions in the country every year at least, so that we can inform programming decisions and be able to effectively target and allocate resources to the most vulnerable communities.

AK: This project (first of its kind in the region) aims to find new and *timely* pathways of measuring poverty in Iraq — looking at how we can utilize what’s already available. Take for example: exploring the use of big data and the data that’s regularly and routinely used by telecoms and other services. So with today’s world of data crunching through algorithms and machine learning — we’re looking to link child poverty and deprivation data with CDR data through machine learning and algorithms, with the hope of further understanding these relationships and predicting trends.

Why leverage mobile data? How does it suit the current context in Iraq? How will leveraging mobile data and technology help to address the challenge you identified?

VS: Phones are everywhere — all around the world, in every type of household — and our seemingly symbiotic relationship with them makes them optimal proxies through which poverty can be estimated. Using mobile phone data to monitor poverty levels is also a non-invasive approach, and requires no added effort or interruption to daily life. More importantly, mobile phone traces give us the potential to create monthly, weekly or even daily snapshots of poverty estimates, yielding an up-to-date picture of where the most vulnerable children live.

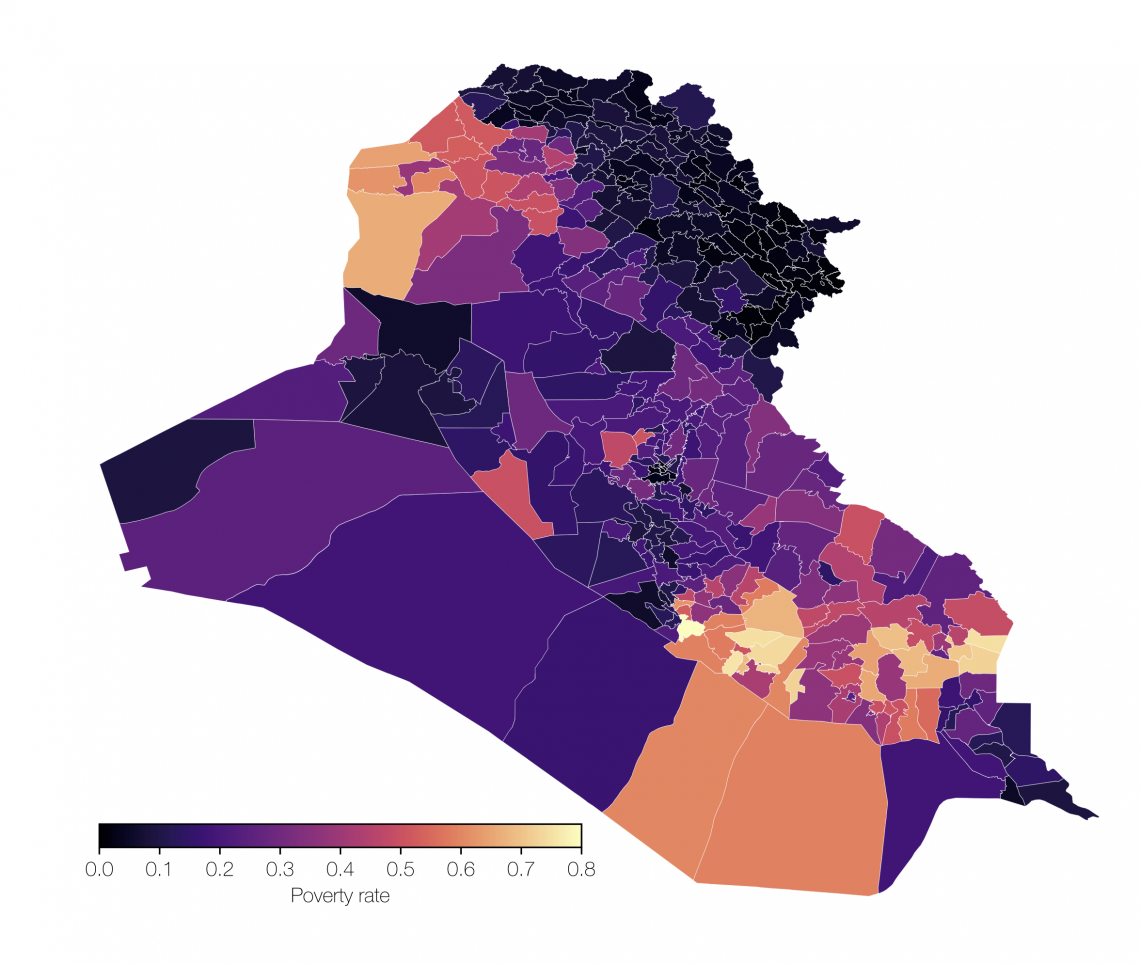

KM: Due to security concerns and challenging access to remote areas in Iraq, it is difficult to gather data from large sample sizes. But mobile networks are already inside almot every Iraqi household, regardless of economic status. That is why leveraging mobile data will make the process easier to deliver the most representative sample in Iraq at Nahiya (admin level 3).

AK: In 2016, Iraq had 101.5 cell phone subscriptions per every 100 persons,1 which is an impressive measure given the type and duration of recent conflicts. While regular poverty estimates have been a challenge, looking at alternative ways of measuring child poverty is a very relevant, timely and necessary idea. Using cell phone data to develop a predictable model to measure child monetary and multidimensional poverty gives tremendous flexibility on when and what to measure. As the model and data become more sophisticated, we could use these tools to identify and measure other relationships (e.g. the impact of drought on populations etc.)

How did the idea get translated into a project – can you share the process from a CO point of view? How did you engage with UNICEF’s Office of Innovation and what does the collaboration look like?

AK: The idea came about after my discussion with Arthur Van Diesen, Social Policy Adviser, Regional Office, MENARO, where we brainstormed (in our annual planning meeting) about the challenges of child poverty measurement and monitoring in Iraq, and how to go about it. We reached out to UNICEF’s Office of Innovation in New York and Antonio Franco Garcia, former Social Policy Specialist in New York, for their guidance in understanding what this project could look like — as well as identifying countries that have similar methods and what their outcomes were, and looking into the potential challenges that we should anticipate.

KM: The collaboration has been very dynamic and productive — even though we are facing a few challenges during implementation due to the difficult country context. The team from the Office of Innovation is very friendly and accessible, doing their best to implement the project in spite of those difficulties. I can predict that this collaboration will create a successful model for the region and one that could be replicated in other countries.

What do you anticipate are the challenges you will encounter and how are you preparing to address these?

AK: One of the challenges we weren’t prepared for was the availability of validated shapefiles (maps of administrative boundaries) at the sub-district or district level. Due to conflict and changes in these administrative boundaries over the years, it was hard to find the maps corresponding to the years 2012 and 2014 that would be used to develop the model.

KM: Working in a challenging environment with no access to data, and where expertise is often limited in the field, can pose some barriers as we go about this project.

VS: A range of challenges exist for this project – one of the most important will be to track down data that temporally aligns with the most recent poverty survey. I.e. we need to know how people called during the last survey to build reliable models. This can be difficult as mobile technology has changed a lot over the past years. Another important challenge is in the actual validation of the model. Fortunately, the government of Iraq is in the process of collecting new survey data for 2018, which we plan to validate our models on.

How do you think this project can make an impact on the programmes that you are implementing in Iraq? How would this bridge your current gaps/challenges?

KM: This project will address the gaps in data generation, which is a serious challenge for Iraq. It can also inform programmes, e.g. on where to direct resources to target the most vulnerable and poorest communities and groups. This project will cover the gaps that exist between costly surveys which are implemented every 4-5 years.

AK: If a predictable and reliable model is developed, this will be a game changer. This will really help improve the availability of data, how many and where poor people live, so that programmes could be tailored to meet their needs and alleviate them from living in poverty.

What partnerships/ organizations (in the public and private space) do you need in place to do this?

AK: Long-term partnerships with telecommunication providers or other companies that have access to relevant data from the population (e.g consumer trends) is essential. Most importantly, their willingness and continued partnership are central to this project.

KM: Specifically, partnering with a local mobile network in Iraq to create the model, and with the Ministry of Planning to use and sustain the model for the longer term.

VS: This project’s partnerships with private partners such as Zain Iraq (and other telcos in the future) are vital if we are to succeed in building a model and keeping it up-to-date. Simply because they have all the data. To make the model mode “correct” we will need to involve other local telcos.

Related Stories